New Jersey hill underappreciated as Washington's hiding place

I grew up in the Watchung Mountains, in Summit to be exact.

Despite the name, the town is not the highest elevation; that distinction belongs to Preakness Mountain in Wayne, near the top of the chain that runs from Campgaw Mountain in Mahwah, to Pill Hill in Far Hills.

If you take your arm and “make a muscle” it mimics the shape of the Watchungs, with the Ramapo Mountains at the fist and the Somerset Hills at the bicep. Summit is at the elbow, so neighborhoods on the northeast side of town look out to New York City and all in between, and on the southwest side, the view takes in Central New Jersey, down to New Brunswick. George Washington used those views to spy on the British.

Tomorrow is July 4th. Independence Day.

And this column is an ode to those mountains, underappreciated by historians — overlooked for their critical role in the revolution. They were Washington’s favorite hiding place, and gave him quick access to iron forges that armed his troops. Their high points allowed him to monitor British troop movements from New York to New Brunswick, and respond by moving men toward conflict behind the safety of the mountains.

Washington spent approximately 3 1/2 years of the eight-year war in and around these mountains, as he moved between the Hudson and Delaware rivers.

There is so much history in these hills, waiting to be remembered.

The Watchungs were a place of great anguish for the Colonial Army: the horrible winter of 1779-80 at Jockey Hollow, when food was so scarce Washington ordered the horses be taken off the camp, so the men wouldn’t butcher them; the smallpox epidemic, which left graveyards of soldiers at churches in Mendham, Succasunna and Basking Ridge; a mutiny in Pompton, which led to the execution of soldiers.

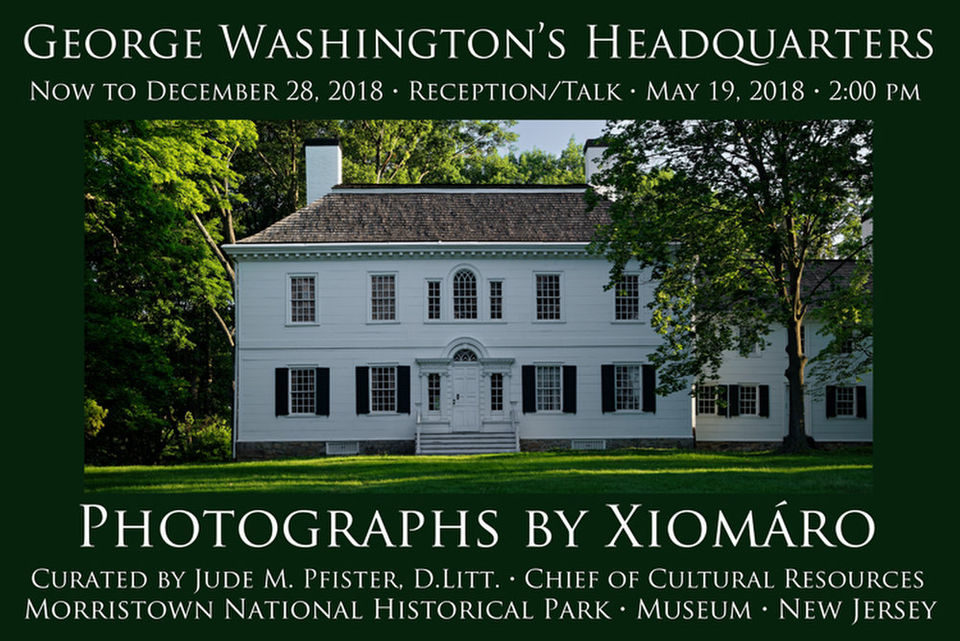

The mountains provided a sanctuary for Continental Army strategy. The nation’s first West Point, an artillery officers’ school, was tucked behind the mountains in Pluckemin, where The Hills development is today. At Morristown, Washington enlisted the French to send Rochambeau and 6,000 troops. From Somerville, he planned Sullivan’s March, a war against Native

Americans in Pennsylvania and New York State. The iron in the western hills beyond the Watchungs was forged into weapons and ammunition, safe from British takeover.

Of course, the New Jersey, as a whole, was also the site of inspirational victories. Trenton and Princeton, which turned the losing tide. Monmouth, the battle that involved the most number of men.

But three lesser known battles were centered around the Watchungs. First was the Battle of Bound Brook, on April 13, 1777, when the British came up from New Brunswick, to attempt to control the upper Raritan River at the base of the mountains. The British were somewhat successful, but not enough to hold the position.

The British again tried to penetrate the mountains during the Battle of Short Hills, in what is today Scotch Plains and Metuchen, on June 6, 1777, after Washington moved his troops from behind the second ridge of the mountains in Morristown, to behind the first ridge at Middlebrook. His headquarters was in the Nathaniel Drake House in Plainfield.

The final British push into the Watchungs came during the Battle of Springfield, in early June of 1780. Under the command of Prussian General Baron Von Knyphausen, 6,000 British, Hessian and Loyalist soldiers maneuvered up what is today Morris Avenue and Vauxhaul Road in an attempt to climb the Hobart Gap and attack Washington in Morristown.

The Gap was a convenient escape/ambush route through the first Watchung Ridge, which Route 24 now climbs at three-lane highway between Summit and Short Hills and descends into Chatham.

They were beaten back, but not before the wife of Rev. James Caldwell, the mother of 10 children, was shot and killed at the parsonage at Connecticut Farms, now Union. The incident is depicted on the Union County seal.

The Battle of Springfield was the last British attempt to conquer New Jersey. Had it been successful, they could have cut the colonies in half and controlled the major ports of the Hudson and Delaware, the two most important rivers in the colonies. After the defeat at Springfield, the British headed south. Washington and the French followed, and the war was coming to an end.

Washington followed the battle from Briant’s Tavern on what is today the Summit-Springfield border.

When I was a young boy, we lived near Briant’s Pond. There was a Newberry’s 5 & 10 in Springfield where there was a mural of Caldwell standing on the steps of a church in front of line of American soldiers saying, “Give ’em Watts, boys!”

My father explained that George Washington was here. This was augmented by unrelated trips to Washington Rock in the South Mountain Reservation and the one at Green Brook to look at the views. Both were lookouts for the general on the first ridge of the Watchung Mountains.

In our town, there was a Beacon Hill Club and a Beacon Hill Road. They overlooked the Hobart Gap. I learned much later – not in school, but as a writer for this paper – that this high outcrop of Watchung rock was the site of one of 23 beacons along the high points of the Watchungs to be lit when “the British were coming.”

The point of all this is education and New Jersey pride.

As I reporter, I learned much more about this history, enough to write a book called “A Guide to New Jersey’s Revolutionary War Trail (Rutgers Press),” detailing over 350 war sites by exact address.

As a proud New Jerseyan, I’ve tried to spread the word, through many columns like this. I urged the state to adopt this slogan, “Do Something Revolutionary, Visit New Jersey.” That was in 1999.

Educating ourselves about this history is as simple as following the geographic lexicon. Many of the Washington streets, sections and schools through the region reflect his presence.

Historic markers from in Bergen, Passaic, Essex, Union, Middlesex, and Somerset counties tell the story of individual places, but nowhere is the whole story of the mountains explained.

So here it is. In our Watchung Mountains, George Washington won the war of attrition. The protection of the hills, and the great swamps that lie between them, kept the British at a long arm’s length for 3 1/2 years of the eight-year war.

Our mountains, which can be seen from all our northern cities and envelopes a great swath of suburbs where at least one-quarter of New Jersey’s population lives, made the war expensive for the British. They were impenetrable.

They are something for us to celebrate today.

I grew up in the Watchung Mountains, in Summit to be exact.

Despite the name, the town is not the highest elevation; that distinction belongs to Preakness Mountain in Wayne. The mountains run from Campgaw Mountain in Mahwah, to Pill Hill in Far Hills.

If you take your arm and “make a muscle” it mimics the shape of the range, with the Ramapo Mountains at the fist and the Somerset Hills at the bicep. Summit is at the elbow, so neighborhoods on the northeast side of town look out to New York City and all in between, and on the southwest side, the view takes in Central New Jersey, down to New Brunswick.

Today is July 4th. Independence Day.

And this column is an ode to those mountains, underappreciated by historians — overlooked for their critical role in the revolution. They were George Washington’s favorite hiding place, and gave him quick access to iron forges that fueled his army. Their high points allowed him to monitor British troop movements from New York to New Brunswick, and respond by moving men toward conflict behind the safety of the mountains.

MORE: Recent Mark Di Ionno columns

George Washington spent approximately 3 1/2 years of the eight-year war in and around these mountains, as he moved between the Hudson and Delaware rivers.

The Watchungs were also a place of great anguish for the Colonial Army: the horrible winter of 1779-80 at Jockey Hollow, when food was so scarce Washington ordered the horses be taken off the camp, so the men wouldn’t butcher them; the smallpox epidemic, which left graveyards of soldiers at churches in Mendham, Succasunna and Basking Ridge; a mutiny in Pompton, which led to the execution of soldiers.

The mountains provided a sanctuary for Continental Army strategy. The nation’s first West Point, an artillery officers’ school, was tucked behind the mountains in Pluckemin, where The Hills development is today. At Morristown, Washington enlisted the French to send Rochambeau and 6,000 troops. From Somerville, he planned Sullivan’s March, a war against Native

Americans in Pennsylvania and New York State. The iron in the western hills beyond the Watchungs was forged into weapons and ammunition, safe from British takeover.

Of course, the New Jersey, as a whole, was also the site of inspirational victories. Trenton and Princeton, which turned the losing tide. Monmouth, the battle that involved the most number of men.

But three lesser known battles were centered around the Watchungs. First was the Battle of Bound Brook, on April 13, 1777, when the British came up from New Brunswick, to attempt to control the upper Raritan River at the base of the mountains. The British were somewhat successful, but not enough to hold the position.

The British again tried to penetrate the mountains during the Battle of Short Hills, in what is today Scotch Plains and Metuchen, on June 6, 1777, after Washington moved his troops from behind the second ridge of the mountains in Morristown, to behind the first ridge at Middlebrook. His headquarters was in the Nathaniel Drake House in Plainfield.

The final British push into the Watchungs came during the Battle of Springfield, in early June of 1780. Under the command of Prussian General Baron Von Knyphausen, 6,000 British, Hessian and Loyalist soldiers maneuvered up what is today Morris Avenue and Vauxhaul Road in an attempt to climb the Hobart Gap and attack Washington in Morristown.

The Gap was a convenient escape/ambush route through the first Watchung Ridge, which Route 24 now climbs at three-lane highway between Summit and Short Hills and descends into Chatham.

They were beaten back, but not before the wife of Rev. James Caldwell, the mother of 10 children, was shot and killed at the parsonage at Connecticut Farms, now Union. The incident is depicted on the Union County seal.

The Battle of Springfield was the last British attempt to conquer New Jersey. Had it been successful, they could have cut the colonies in half and controlled the major ports of the Hudson and Delaware, the two most important rivers in the colonies. After the defeat at Springfield, the British headed south. Washington and the French followed, and the war was coming to an end.

Washington followed the battle from Briant’s Tavern on what is today the Summit-Springfield border.

When I was a young boy, we lived near Briant’s Pond. There was a Newberry’s 5 & 10 in Springfield where there was a mural of Caldwell standing on the steps of a church in front of line of American soldiers saying, “Give ’em Watts, boys!”

My father explained that George Washington was here. This was augmented by unrelated trips to Washington Rock in the South Mountain Reservation and the one at Green Brook to look at the views. Both were lookouts for the general on the first ridge of the Watchung Mountains.

In our town, there was a Beacon Hill Club and a Beacon Hill Road. They overlooked the Hobart Gap. I learned much later – not in school, but as a writer for this paper – that this high outcrop of Watchung rock was the site of one of 23 beacons along the high points of the Watchungs to be lit when “the British were coming.”

The point of all this is education and New Jersey pride.

As I reporter, I learned much more about this history, enough to write a book called “A Guide to New Jersey’s Revolutionary War Trail (Rutgers Press),” detailing over 350 war sites by exact address.

As a proud New Jerseyan, I’ve tried to spread the word, through many columns like this. I urged the state to adopt this slogan, “Do Something Revolutionary, Visit New Jersey.” That was in 1999.

Educating ourselves about this history is as simple as following the geographic lexicon. Many of the Washington streets, sections and schools through the region reflect his presence.

Historic markers from in Bergen, Passaic, Essex, Union, Middlesex, and Somerset counties tell the story of individual places, but nowhere is the whole story of the mountains explained.

So here it is. In our Watchung Mountains, George Washington won the war of attrition. The protection of the hills, and the great swamps that lie between them, kept the British at a long arm’s length for 3 1/2 years of the eight-year war.

Our mountains, which can be seen from all our northern cities and envelopes a great swath of suburbs where at least one-quarter of New Jersey’s population lives, made the war expensive for the British. They were impenetrable.

They are something for us to celebrate today.

Mark Di Ionno may be reached at mdiionno@starledger.com. Follow The Star-Ledger on Twitter @StarLedger and find us on Facebook.

http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2018/07/how_the_watchung_mountains_won_the_revolution_di_i.html